driven investing: How I made 33x my money in two weeks

Event-driven investing: How I made 33x my money in two weeks

My favorite part of the book ‘The Big Short’ is the narration Lewis gives of Jamie Mai and Charlie Ledley’s investment strategy at Cornwall Capital Management. Over a period of four years from 2002 to 2006, the hedge fund famously grew from two friends operating out of a Berkeley garage with $110,000 “in a Schwab account”

Event-driven investing

At the tender age of 30 neither Jamie or Charlie had much experience with managing money, or even making actual investment decisions on their own. From their brief stints working in private equity, the only tangible experience they had come away with were two views of the world which would eventually end up guiding their investment decisions:

- Public markets are less efficient, due diligent and prudent than private markets; and

- Investors in public markets as a consequence typically end up with much narrower interests and focus, often missing the bigger, overall picture of what is going on.

In other words, in their view, mechanisms in the public market were most always likely to be more flawed and prone to erroneous assumptions and/or calculations than mechanisms in private markets.

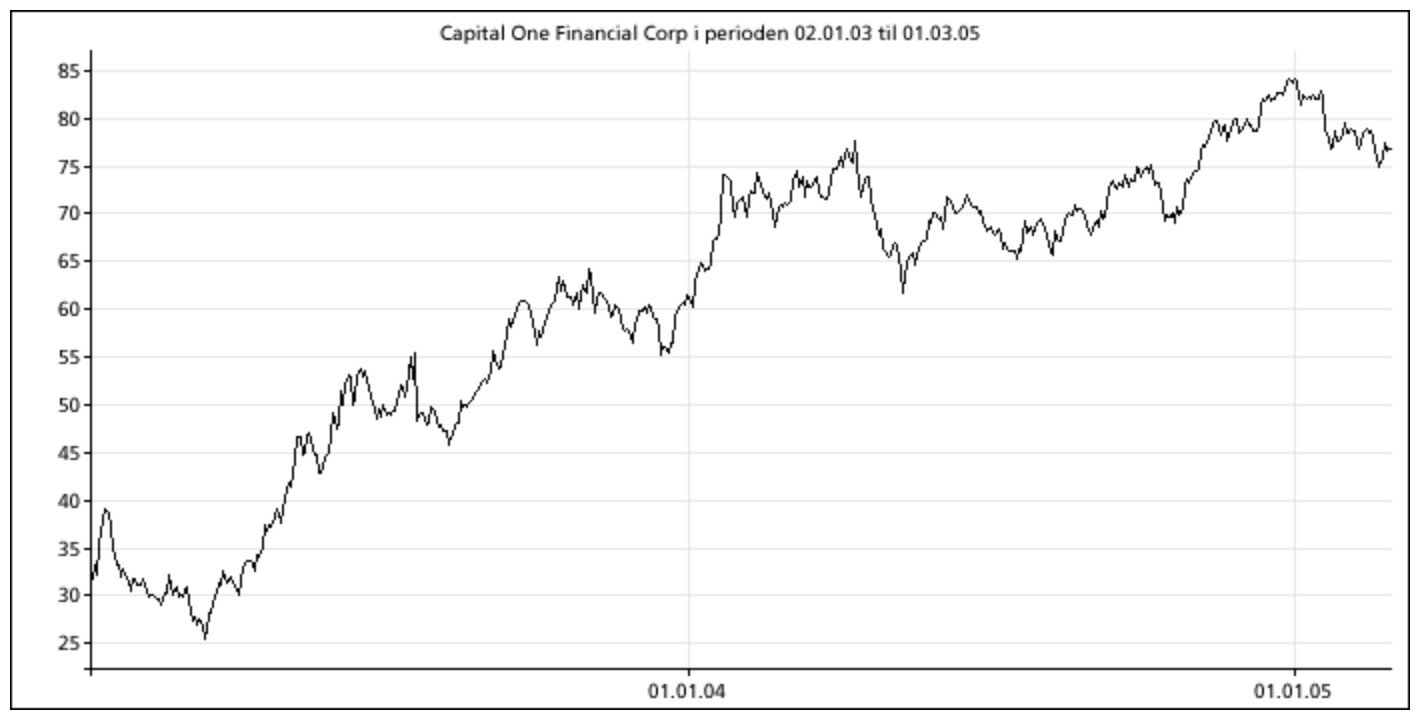

Taking their view of the world to the market, Cornwall Capital first hit it big when they came across a subprime credit card company named Capital One whose stock had dropped 60% in two days from speculations about how much collatoral the company should be holding and accusations of fraud among the company’s directors.

And although the company’s financial performance seemed stellar and nothing had yet materialized from the SEC’s investigation — the stock didn’t seem to want to move. To understand why, Jamie and Charlie did their own due diligence of the firm and eventually decided that: 1. Either the company was run by crooks and was worthless; or 2. The company had strong fundamentals and its stock was vastly undervalued by the market. Regardless of which was true, they knew that the stock shouldn’t be trading at the level that it was at the time.

Inflection points

This wonderfully binary situation meant that there was going to be a big fork in the road for Capital One’s stock in the short to medium term, as their regulator would reach its verdict about what was going on internally. When this occurred, the stock would undoubtedly experience an inflection point, moving rapidly and markedly either up or down.

In the options market, where one ventures into contracts about rights to buy or sell anunderlying asset at a predetermined price on or before a given date, prices are initially determined based on mathematical models. Underpinning such models, are a set of assumptions about things like volatility, the efficiency of the market, dividends, interest rates, distribution of returns and liquidity.

In situations where the future price of a stock is strongly correlated to something akin to a binary (either/or) set of events which is likely to cause an inflection point, it turns out that the assumptions underpinning such models tend to break down. In other words, although a stock’s rise or fall over the course of a future period of time certainly isn’t consistent with constant volatility or gaussian distribution of returns, its options (especially longer term options) may still be priced as if though they were.

For Jamie and Charlie, who eventually decided for themselves that Capital One was not run by crooks, that meant that if their assumptions were true, their $26,000 in long term call positions (LEAPS) had been bought at an extraordinary discount. Sure enough, as the company was vindicated by the SEC its share price inflected up to pre-crisis levels and Cornwall Capital’s option position appreciated in value to $526,000.

Asymmetric investments

What attracts me to Jamie Mai and Charlie Ledley’s investment thesis is the extraordinary asymmetry that existed between the potential upside of gains relative to the level of downside risk. Stemming from its event-driven nature, the strategy makes use of the disconnect that can exist between prices set by mathematical models and the valuation made by a rational investor. Being outside of the 95th percentile of most VaR (value at risk) models, the likelihood of such events occurring are simply viewed as so unlikely that they are discounted in the pricing that the model makes (read: The Financial Crisis of 2007–08).

And so, rather than buy the Capital One stock and hope it would appreciate back up to $60 (approximately 75% returns), wrongly priced option contracts instead earned Jamie and Charlie a 2000% return on their investment.

My first options trade, ever

Never really having bought or sold any financial instruments besides stocks, three weeks ago I was completely new to the mechanics and practicalities of options trading. However, as losses were mounting in early 2016, I had been tracking the prices of a few oil service companies who were taking big hits as the price of oil was declining. One such company, Seadrill ($SDRL), was being particularly hammered by short sellers, dropping from NOK31 to NOK15 in under a month.

With overall depreciation of 95% over the previous three years, a bleak outlook for the industry, debts maturing and nothing on the horizon that seemed likely to encourage investment, the stock’s options prices showed a similarly negative outlook. On the 22nd of February, with the price of the underlying asset at NOK15.4, an American call option expiring on 06/16 with strike price NOK30 could be bought for the mere sum of NOK0.55 per contract, 350 basis points. And so I did.

My thinking was very simple. Looking at how the stock had depreciated over the past two years and how it reacted to daily fluctuations in the price of oil I decided for myself that the market viewed the two as strongly correlated. Calculating this correlation ratio at various points in the period, I could see what I thought to be (at least) a superficial relationship between the two prices, which I determined to be that: if the price of oil went from its current level of $37 per barrel, to say, $45, the Seadrill stock would move to $27. Needing to cover their bets, many short sellers would at this point likely be squeezed, which could cause the price to soar higher.

What I essentially bought for NOK0.55 per contract, was a lottery ticket on the price of oil. Except instead of there being one drawing of numbers, every day from the 22nd of February to expiration on the 16th of June, the price could potentially be going up. And instead of betting on random numbers, I was betting on geopolitics, macro economical uncertainty and a company whose stock had been hammered so hard that even the slight hint of some good news was fueling weekly spikes in its share price of several percent.